Why sexual assault case against Duke of York could be nightmare for royals and

Scotland Yard

- The

former Duke of York has become a virtual exile in the UK, for fear of

extradition. UK law is even more strict than US, where under the Sexual

Offences Act 2003, a claimant is to be believed, regardless of the lack

of any proof, other than the say so of a claimant. This reverses the

Article 6 protections, where a person is to walk into a court innocent,

until proven guilty. In the UK, you are guilty until proven innocent.

The UK, with Her

Majesty Queen Elizabeth as head of state, is guilty of removing the

human rights of those accused of sexual offences in the UK. This statute

was enacted after development by David

Blunkett. In an ironic twist of

fate, it now appears that the Queen's 2nd born son, may have fallen foul

of rules designed to increase conviction rates, regardless of innocence

or guilt - though in the US. This is called noble cause corruption. The

Crown does not mind filling prisons with an extra quota of men and

women, around 3-5% of which are more than likely innocent - because the

State has also deprived them of any effective remedy, by removing

Article 13 from the HRA 1998, and cutting Legal Aid to the point where

it is impossible to mount a comprehensive defence. They have thus

anticipated the effect their rule bending will cause, and cut off any

path to justice for those wrongly convicted.

HANSARD DECEMBER 2020 - Dame Diana Johnson (Kingston upon Hull North) (Lab)

I beg to move,

That leave be given to bring in a Bill to criminalise paying for sex; to decriminalise selling sex; to create offences relating to enabling or profiting from another person’s sexual exploitation; to make associated provision about sexual exploitation online; to make provision for support services for victims of sexual exploitation; and for connected purposes.

This is a Bill to bust the business model of sex trafficking. Today, the UK is a high-value, low-risk destination for sex traffickers. Why? Because our law fails on two critical fronts: first, it fails to discourage the very thing that drives trafficking for sexual exploitation—demand—and secondly, it allows ruthless individuals to facilitate and profit from sexual exploitation. What does this mean in practice? It means that the minority of men in England and Wales who pay for sex do so with impunity, fuelling a brutal sex trafficking trade and causing untold harm to victims. It also means that profit-making pimping websites operate free from criminal sanction, helping sex traffickers to quickly and easily advertise their victims and reaping enormous profits from doing so.

Right now there is a sexual-exploitation scandal playing out in towns and cities across the UK. An inquiry by the predecessor of the all-party parliamentary group on commercial sexual exploitation, which I chair, found that the UK sex trade is dominated by organised crime, with sex trafficking taking place on an industrial scale.

HUMAN'S

SEXUAL FUTURE WITH ROBOT AIDS - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In 2017 most liberal societies accept or tolerate sex in many different forms and varieties. Sex toys and masturbation aids have been used for centuries and can be easily purchased in many countries. Now the sale of robots developed for sexual purposes is fast approaching. A number of companies such as Realbotix, Android Love Dolls, True Companion and the Sex Bot have begun to take shipping orders. Most of the robots are gendered as female models with pornographic bodies although some are male. If this turns out to have market success, we can expect more companies to follow suit.

There has been little or no preparation for the potential societal consequences. Robots designed for sex may have powerful impacts on society compared with other sex aids. They could be used as robot ‘prostitutes’ working in bordellos, sexual companions for the lonely or the elderly in care homes or as a new means for sexual healing. On the darker side, they could be employed to satisfy rape fantasies or even to satisfy paedophilic desires. In response, the FRR has issued the first major consultation report on our sexual future with robots. The aim is to provide the public and policy makers with an objective summary of the issues and the various opinions about what could be our most intimate association with technological artefacts. We do not contemplate or speculate about distant future robots that could have all manner of imagined properties. We focus instead on significant issues that may have to be dealt with in the foreseeable future.

The report examines the state of the art in sex robots and the relationship to parallel developments in sextech such as teledildonics. This leads us to expect the remote use of sex robots for couples and groups and the use of AI for heightening orgasms. The report then focuses on seven questions that need to be asked about the technology:

1. Would people have sex with a robot

The success of silicon sex dolls for sexual gratification has set a clear path for the role of

robotics in the future of sex. Public polls and indirect measures suggest that there would be a market for sex robots. A small to medium percentage of people indicate that they would consider having sex with a robot. There were a smaller number of women than men but still a significant number showed interest. We cannot say yet how large the market will be. It could be a niche for fetishists, a new paraphilia, or societal norms could alter to allow their use to become widespread.

2. What kind of relationship can we have with a robot?

We turn to moral philosophers, scientist and sex workers to compare differences between human relationships and what robots offer. Robots cannot feel love, tenderness, or form emotional bonds. All that can be afforded at this time are fictive relationships based on pretence and fantasy – a willing suspension of disbelief. The best that robots can do is to ‘fake it’. They will not have the full presence and engagement required for ‘complete sex’ in which we desire to be desired. But anthropomorphic features and ‘faking it’ might be enough for some people as evidenced by existing fictive relationships between a few men and their silicon sex dolls.

3. Will robot sex workers and bordellos be acceptable?

We look at evidence from the success of brothels with sex dolls – the precursors of sex robots. These started in Asia, were quickly accepted, and the numbers are now increasing. A Lumidoll brothel has recently opened in Europe with big plans for expansion. The same bordellos could gradually upgrade their stock with robotic dolls without raising any further eyebrows.

4. Will sex robots change societal perceptions of gender?

There is little question that creating a pornographic representation of women’s bodies in a moving sex machine will objectify and commodify women’s bodies as well as perpetuate the notion of easy sex on demand. However, the big question is, what additional impact on societal perception will this create within an already burgeoning adult industry that thrives on such objectification and commodification? It may be an amplifier but we just don’t know yet.

5. Could sexual intimacy with robots lead to greater social isolation?

The majority of experts reviewed in the report provide strong arguments that sex robots could lead to some form of social isolation. This is contrary to what the manufactures of sex robots tell us. The CEO of RealBotix says that he has been making sex dolls for many years especially to alleviate the loneliness of those who, for whatever reason, have problems relating to human intimacy. The public survey data shows mixed opinions.

6. Could robots help with sexual healing and therapy?

No one is claiming that sex robots would be a panacea for all sexual concerns or difficulties. It is possible that the use of sex robots in some therapies could potentially help with sexual healing. For example, it may be beneficial to use a robot for personal private practice in the treatment of problems such as impaired sexual functioning or social anxiety about sex. All adults are entitled to a sex life and sex robots have also been proposed as a means of gratification for the disabled and the elderly. This idea poses some complex ethical issues, particularly with the elderly in care homes, that should be resolved before use.

7. Would sex robots help to reduce sex crimes?

Child sex dolls have already been developed for paedophiles to use and there are the beginnings of sex robots that are resistant to sexual advances to enable the enactment of rape fantasies. The question of using these as a means to prevent first offences or recidivism has led to severe disagreements. Some believe that expressing disordered or criminal sexual desires with a sex robot would satiate users to the point where they would not have the desire to harm fellow humans. Alternatively, many others believe that this would encourage and reinforce illicit sexual practices and make them more acceptable. Allowing people to live out their darkest fantasies with sex robots could have a pernicious effect on society and societal norms and create more danger for the vulnerable.

LEGALISED PROSTITUTION - Is prostitution legal in the UK?

Prostitution describes the offering and provision of sexual services for financial gain.

In the UK, with the exception of Northern Ireland (where buying sex is illegal), the law around prostitution is considered a grey area.

Prostitution itself is not illegal but there are a number of offences linked to it. For example it is an offence to control a prostitute for gain, or to keep a brothel.

Which countries legalise prostitution?

Currently there are a number of different legal frameworks in existence around the world in relation to prostitution. The three most cited are:

Legalisation

The legalisation model is the one followed in Austria, Germany and the Netherlands.

Prostitutes are classified as independent workers. They need to register, obtain a permit, and pay tax in order to work legally. Sex work is thus legalised, but regulated, with the aim of preventing exploitation, improving the conditions of sex workers, and reducing links with organised crime.

Critics of this approach include the group, the English Collective of Prostitutes who claim it benefits those running sex businesses rather than those working in them. They claim that a second clandestine tier of prostitution is driven underground, and that this leads to unsafe conditions for those involved.

It is also claimed that many prostitutes do not want to register under a legalised system as it threatens their anonymity.

Decriminalisation

Decriminalisation is the choice supported by many sex worker campaign groups, but also by Amnesty International, the World Health Organisation, and the Royal College of Nursing.

Decriminalization of prostitution is the regime operated in some American States, and in New Zealand. New Zealand is the only country in the world that takes this approach at a national level.

Decriminalisation removes all laws related to prostitution. It is said to allow sex workers to take control of their industry and help eliminate the exploitation that may exist with it. The New Zealand government has claimed that since sex work was decriminalised, trafficking has been all but eliminated, and 70% of sex workers say they are more likely to report violence to the police.

Critics of this approach argue it does do not solve larger issues like sexual exploitation, child prostitution, social and gender inequality, nor eliminate social stigma.

The Sex Buyer Law

This is also known as the Nordic Model. It aims to end the demand for, and thus eliminate, prostitution. Under the Nordic model, it is not illegal to sell sex, but it is illegal to buy it.

Supporters of this approach argue that prostitution can never be made safe or ever get close to the United Nation’s definition of ‘decent work’.

Critics of this approach argue that it fails to take account of the effects that this kind of legal framework has on the safety of sex workers, with many prostitutes simply being driven to operate further underground.

This system is in operation in Sweden, Norway, Iceland, France, Ireland, and Northern Ireland.

The political arguments around prostitution in the UK

As with all matters of sexuality, prostitution continues to be debated on both social and moral levels.

Social conservatives believe that prostitution is intrinsically and morally corrupt, and that it represents a challenge to family values. Many religious groups support making prostitution illegal, adding a further aspect to the debate. Leading feminists and women’s groups also favour legal controls, arguing that prostitution is degrading and exploitative in its nature.

Opponents of prostitution also argue that because prostitutes have large numbers of sexual partners, they are more likely to have sexually transmitted infections and be vectors for spreading these infections – adding a public health dimension to the debate.

Prostitution’s quasi-criminal status has led it to be closely associated with organised crime, poverty, drugs, child abuse and people trafficking. Modern slavery has risen up the political agenda in recent years, and this has again been linked with prostitution. There has been an increase in the ‘white slave trade’ from Eastern Europe and Russia, along with a general influx of organised crime, with many women being seen to live as virtual slaves.

On the other side of the debate, there are others who are argue that prostitution is a matter of personal choice between consenting adults. It is therefore not a matter for the state, or the criminal law.

Many of those who regard prostitution as a matter of private morality, do though still argue for legal regulation. Some argue that licensed brothels would help to ensure safety, taking sex workers off the streets and into more secure environments.

Others suggest the formal regulation of prostitution would help prevent health problems, bring in revenue to the Treasury through taxation, and remove the need for exploitative and abusive pimps.

A History of prostitution in the UK

The current legal framework in the UK does not clearly fall into the categories of legalisation, decriminalisation, or the Nordic model seen in other countries. This is how the legal regime has developed to date:

Early History

Prostitution is regularly referred to as ‘the oldest profession’, based on the suggestion that it meets the natural urges of humans in return for money. It is often claimed to be as old as civilisation itself.

In the Nineteenth Century, the Contagious Diseases Act of 1864 made it the law for women suspected of prostitution to register with the police and submit to an invasive medical examination. The Act was repealed in 1886.

Prostitution law in the UK was then further set out in the Sexual Offences Act 1956, which reflected the findings of the Wolfenden Committee.

The Wolfenden Committee had been set up in response to the increasing visibility of prostitutes in London during the early 1950s, along with an increase in the number of homosexual offences and media scandals being reported in the press at the time.

The Wolfenden Committee treated prostitution and its status in the law as a moral issue and this was reflected in the text of the 1956 Sexual Offences Act. This led to famous debates between Lord Devlin and the philosopher Herbert Hart. Stricter controls of street prostitution were recommended by the report, and these were put into effect in the Street Offences Act of 1959.

Early 2000s

In 2001, the Criminal Justice and Police Act 2001 created an offence to place advertisements relating to prostitution on, or in the immediate vicinity of, a public telephone box.

This provision was though to become less relevant in time with the emergence of mobile phones and the growth of the internet.

In terms of prostitution policy, the then Labour government said it wanted to reduce prostitution in the UK, but argued that legal controls were too blunt a tool. Instead in 2002 the Government made a total of £850,000 available for groups working in a multi-agency context to implement local strategies for reducing prostitution-related crime and disorder.

In late 2003, the Home Office announced its intention to review the laws on prostitution with the aim of overhauling the dated regulations of the 1956 Act. Subsequent amendments relating to prostitution were made under the

Sexual Offences Act 2003 with regard to the following offences; “causing or inciting prostitution for gain”, “controlling prostitution for gain”, “penalties for keeping a brothel used for prostitution” and “extension of gender specific prostitution offences”.

The murders of five prostitutes in Ipswich in November and December 2006 reignited calls for a new approach to tackling the issue.

In November 2008, the Home Office published the findings of a six month review into how the demand for prostitution could be reduced. Home Secretary Jacqui Smith, in a foreword to the review, stated: “So far, little attention has been focused on the sex buyer, the person responsible for creating the demand for prostitution markets. And it is time for that to change.”

But Government plans to create a new law under the Policing and Crime Bill, making it an offence to pay for sex with someone who is “controlled by another for gain”, caused particular controversy. Even if the person paying for sex was unaware that the prostitute was trafficked or controlled by a pimp, they would still be liable for prosecution and if convicted would be given a criminal record and a fine of up to £1,000.

The Bar Council warned that the offence as drafted risked convictions that may be seen as unfair by reasonable people and that such convictions would bring the criminal law into disrepute, particularly given the stigma that would result.

The Policing and Crime Bill, introduced to the Commons in December 2008, created a new offence of paying for sex with someone who is controlled for gain, and subjected to force, coercion or deception. The Act also introduced new powers to close brothels.

The Policing and Crime Act 2009 also modified the law on soliciting. It created a new offence for a person to persistently loiter in a street or public place so to solicit another for the purpose of obtaining a sexual service as a prostitute. The reference to a person in a street or public place includes a person in a motor vehicle in a street or public place. This replaced the offences of kerb crawling and persistent soliciting under sections 1 and 2 of the Sexual Offences Act 1985 with effect from 1 April 2010.

Since 2010

The Coalition government was strongly criticised in the Spring of 2010 for declining to support a proposal for an EU directive to prevent and combat trafficking in human beings and to protect the victims who were trafficked for different purposes, including into the sex industry.

The Government did, however, promise to review its decision when the finalised text was agreed and in March 2011, having scrutinised the final text, announced that it would now apply to opt in to the new EU directive (2011/36/EU) on trafficking in human beings.

In December 2011, the Home Office launched a national ‘Ugly Mugs’ pilot scheme to help protect sex workers from violent and abusive individuals. The Home Office provided £108,000 to fund the 12 month pilot which included establishing a national online network to bring together and support locally run ‘Ugly Mug’ schemes.

These local ‘Ugly Mug’, or dodgy punter schemes as they were labelled, have been running for some years and, according to the UK Network of Sex Work Projects, have proved very useful in passing on warnings to sex workers about dangerous people, as well as helping to increase the reporting, detection and conviction of crimes.

In March 2012, the Greater London Authority published a report on the policing of off-street sex work and sex trafficking in London. Entitled ‘Silence on Violence – improving the safety of women’, the report was written by Assembly Member Andrew Boff at the request of the then London Mayor,

Boris

Johnson.

Mr Boff found evidence that sex workers were reporting fewer crimes to police and that raids had increased in some parts of London. He made a number of recommendations including involving sex workers in police strategies that involve them, and around prioritising crime against sex workers by labelling it as a hate crime.

In 2014, the House of Commons All-Party Parliamentary Group on Prostitution and the Global Sex Trade undertook an inquiry into the current legal framework around prostitution in the UK. Their report concluded, “the law is incoherent at best and detrimental at worst. The legal settlement around prostitution sends no clear signals to women who sell sex, men who purchase it, courts and the criminal justice system, the police or local authorities”.

The group recommended the introduction of a ‘sex buyer law’ to shift “the burden of criminality from those who are the most marginalised and vulnerable – to those that create the demand in the first place”.

This report was followed up by a 2016 inquiry by the Commons Home Affairs Select Committee. The inquiry investigated the varying approach of countries that had both legalised prostitution and brought in sex buyer laws. The Committee’s report did not recommend either of the two options and called for more evidence to be made available around this particular debate.

Responding to the Select Committee, the government agreed there was a need for greater evidence and allocated £150,000 to the University of Bristol to lead this research. The then Home Office minister Victoria Atkins stated that the Government’s focus “remains on protecting those selling sex from harm and enabling the police to target those who exploit vulnerable people involved in prostitution”.

Prostitution UK Quotes

“The existence of prostitution in our society is a highly emotive issue that often polarises opinion and prompts passionate debate, with a range of views and positions. For example some people will argue that prostitution is an inherently exploitative activity and should be challenged at every level and demand a zero tolerance approach, others have a position that engaging in sex work is a matter of personal choice for individuals who need to be protected and respected by the Police Service and wider society” – The National Police Chiefs’ Council operational guidance for police forces to follow when responding to prostitution, National Policing Sex Work Guidance, December 2015.

“There is a group in London who are at least 12 times more likely to be murdered than the national average. Approximately three quarters of those within this category will also be subjected to violence, assault and rape. However this group often distrusts the police and are much less willing to report crimes against them than the national average. he group referred to are sex workers and it is imperative that we improve their safety in London.” – Andrew Boff, Leader of the Conservative group in the London Assembly – 2012.

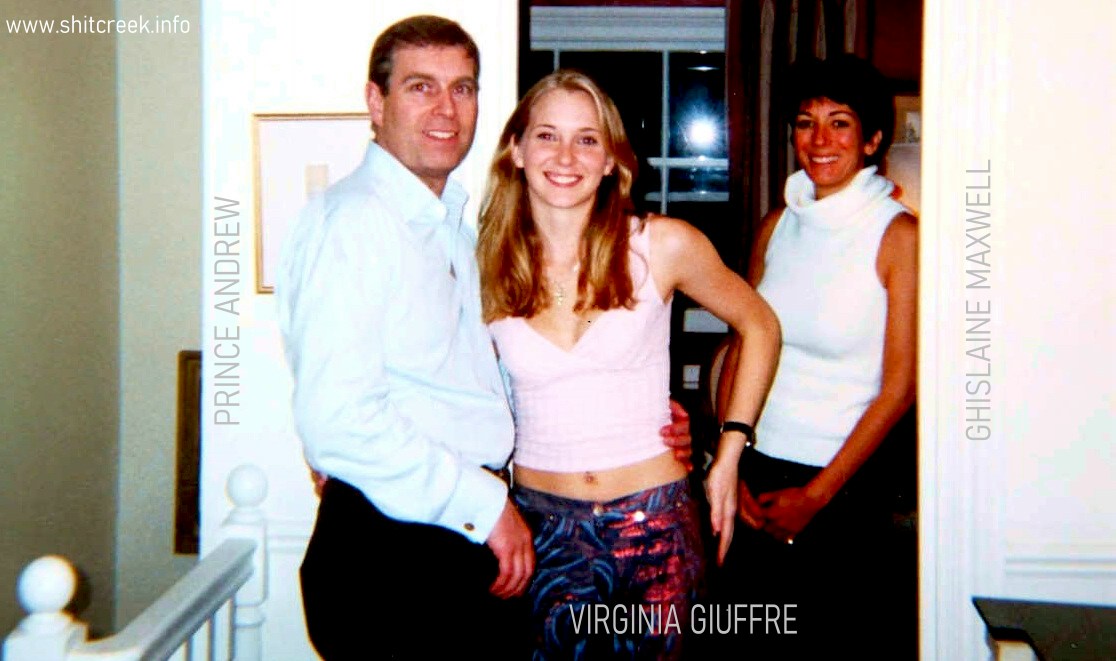

ROYAL

PICKLE - CAUGHT WITH HIS TROUSERS DOWN

Andrew

Brettler is the attorney acting for Andrew

Mountbatten-Windsor agaist Virginia (Roberts)

Giuffre, in the case

of alleged rape when his client was a minor under US law, where the age

of consent is 18, but just rape in the UK, where the age of consent is

16. The

lawyer representing Virginia

Giuffre, is David

Boise.

That

means that according to US law, women in the US are less intelligent

than those in England. It also means that women is Spain and France are

much more advanced in their thinking than in America or Britain.

We

wonder how that is possible, where the more advanced civilizations,

appears to be the more retarded in saying that their children are not

that well informed. I.e. incapable of giving consent.

Or

is that to do with older women's rights. Those who might otherwise be left on

the shelf one year earlier. Food for thought.

It

is an indictment of the promiscuous age we live in perhaps. With the

more permissive society, seeking to stave off penetration of their

children with threats of imprisonment, for as long as possible, to

preserve their shelf life.

This

is surely a case for artificial sex

companions if ever there was one.

The

real bone of contention is surely not age, but rape. That the events

took place without the consent of the girls in question, and that it is

alleged, that they were trafficked. In other words they were forced into

a life of prostitution. If so, Virginia seems to have done pretty well

out of it!

If

so, what was the going rate? How did they keep the girls secured. Were

they locked up drugged and beaten, or were they willing participants -

looking to play the odds - the moment an opportunity arose?

See

12th January decision:

Judge Lewis Kaplan said he should be able to make a decision "pretty soon"

as to whether Virginia

Giuffre's sex assault civil lawsuit against Prince Andrew should be dismissed.

Prince Andrew, now Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor, is currently defending

the sexual assault lawsuit from Virginia Giuffre, who says the convicted sex criminals

Jeffrey Epstein and

Ghislaine Maxwell “forced” her to have “sexual intercourse” with the

then Duke of York – an accusation that Andrew adamantly denies, but

has so far failed to redress with any kind of solid evidence.

THE INDEPENDENT 5 JANUARY 2022 - VOICES: PRINCE ANDREW MAY NOT NEED TO SWEAT ANY LONGER

What a day to be Judge Lewis Kaplan, the district judge serving on the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York – the man with the fates of Virginia Roberts Giuffre and Prince Andrew in his hands, and the eyes of the world upon him.

CPS - PROSTITUTION & EXPLOITATION OF PROSTITUTES

- Overall approach to the prosecution of Prostitution

The CPS focuses on the prosecution of those who force others into prostitution, exploit, abuse and harm them. Our joint approach with the police, with the support of other agencies, is to help those involved in prostitution to develop routes out.

The context is frequently one of abuse of power, used by those that incite and control prostitution - the majority of whom are men - to control the sellers of sex - the majority of whom are women. However CPS recognises that these offences can be targeted at all victims, regardless of gender.

The CPS charging practice is to tackle those who recruit others into prostitution for their own gain or someone else’s, by charging offences of causing, inciting or controlling prostitution for gain, or trafficking for sexual exploitation. In addition to attracting significant sentences, these offences also provide opportunities for seizure of assets through Proceeds of Crime Act orders and the application of Trafficking Prevention Orders.

For those offences which are summary only (loitering and soliciting, kerb crawling, paying for sexual services and advertising prostitution) the police retain the discretion not to arrest or report to the CPS those suspected of committing an offence, or they can charge the offence without reference to a prosecutor, regardless of whether the suspect intends to plead guilty or not guilty.

Introduction

- This guidance provides practical and legal guidance to Prosecutors dealing with prostitution-related offences.

Prostitution is addressed as sexual exploitation within the overall CPS Violence against Women and Girls (VAWG) portfolio, due to its gendered nature. See Violence Against Women and Girls, elsewhere in the Legal Guidance. The individual policies that sit within the VAWG framework will be applied fairly and equitably to all perpetrators and victims of crime, regardless of gender.

The CPS works closely with the police on all prostitution-related offences. The National Police Chief’s Council (NPCC) National Guidance on Policing Sex Work was published in December 2015.

Prosecutors should be aware that there is autonomy as to how forces police prostitution within their area. For those offences which are summary only – loitering and soliciting, kerb crawling, paying for sexual services, keeping a brothel and advertising prostitution – the police retain the discretion:

- Not to arrest or report to the CPS those suspected of committing an offence;

- To charge the offence without reference to a Prosecutor, regardless of whether the suspect intends to plead guilty or not guilty;

- To issue a simple caution to a suspect;

- To decide that no further action should be taken; or

- To issue a conditional caution if they consider that the suspect might be suitable.

However, the police guidance provides practical advice when dealing with prostitution-related issues to ensure consistent levels of service, whilst balancing the need to protect those involved in prostitution from crime. The strategic principles for policing prostitution emphasise that those who sell sex should not be treated as offenders but as people who may be or become victims of crime. Prostitution should be tackled in partnership with other organisations and projects offering support services.

The Police guidance recognises the diverse nature of prostitution and the different challenges in responding. It also emphasises the need to robustly investigate organised criminal activity associated with sexual exploitation. This CPS guidance provides links to other legal guidance associated with exploitation of prostitution, including trafficking for sexual exploitation, drugs and domestic abuse.

Whilst historically, case-law and legislation detailed below used the female gender when setting out offences, for present-day purposes it should be noted that the law encompasses everyone.

Public interest considerations

When considering charging, in addition to the public interest factors set out in the Code for Crown Prosecutors, the following public interest aims and considerations should be borne in mind:

- Those who sell sex should not be routinely prosecuted as offenders. The emphasis should be to encourage them to engage with support services and to find routes out of prostitution.

-

Diversionary approaches should be prioritised over enforcement of offences under the Policing and Crime Act 2009, which should only be used as part of a staged approach that includes warnings and cautions.

-

It will generally be in the public interest to prosecute those who abuse, harm, exploit, or make a living from the earnings of prostitutes.

Generally, the more serious the incident and previous offending history, the more likely it is that a prosecution will be required.

When considering cases of sexual exploitation of a child, Prosecutors should refer to relevant legal guidance on ‘Child Sexual Abuse’. Coercion and manipulation often feature in these cases and the focus should be on prosecuting those who exploit and coerce children, with the child being treated as a victim. For those who sexually abuse children, offences under Sections 47–51 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003 should be considered. See Sexual Offences Act 2003 – Guidance, elsewhere in the Legal Guidance.

Drugs, Alcohol and Other Vulnerabilities

There can be strong links between prostitution and problematic substance (drug and alcohol) use, on a number of levels. For example, such usage can be a coping mechanism for people involved in prostitution. For others, it can be an addiction funded by the prostitution itself. On the other side of the spectrum, it can be a method to embroil and coerce another into prostitution.

Other vulnerabilities of those who sell sex may include mental illness and depression, homelessness or vulnerable housing status, domestic abuse and previous experience of the criminal justice system. Suitable cases should be dealt with by means of diversion from the criminal justice system, with referral to special exiting and outreach support. This would include mental health support, benefits advice, education, training and employment support, drug and alcohol services, health services and domestic abuse services.

Links with Human Trafficking

Human trafficking is a lucrative business and is often linked with other organised crime within the sex industry, covering criminal activities such as immigration crime, violence, drug abuse and money laundering. Victims may be targeted for sexual exploitation because of their immigration status, economic situation or other vulnerabilities.

Those who sell sex are often targets of violent crime, which can include physical and sexual attacks, including

rape. Evidence suggests that offenders deliberately target those who sell sex because they believe they will not report the crime to the police. Perpetrators of such offences can include clients or pimps. There is a strong public interest in prosecuting violent crimes against those who sell sex. In circumstances where a person who sells sex has reported a criminal offence and decided to support a prosecution, special measures should be considered at the earliest opportunity to give them the necessary support and confidence to provide evidence, including through the use of ABE interviews.

Prosecutors should be alert to Section 41 Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act 1999, which protects complainants in proceedings involving sexual offences by placing restrictions on evidence or questions about their sexual history. In cases where physical or sexual violence is used, the Defence is likely to seek to adduce evidence of the complainant’s previous sexual history. The Court may give leave in relation to any evidence or question only on an application made by or on behalf of an accused. Subsections (2)-(6) set out the circumstances in which courts may allow evidence to be admitted or questions to be asked about the complainant's sexual behaviour.

Those involved in prostitution may face violence from their partners, especially if they are also controlling their activities. Although these cases may be difficult to identify and prosecute, Prosecutors should be alert to this fact and consider whether domestic and sexual abuse is being used as a form of control and whether or not charges could be instigated against the perpetrator. The CPS guidance on prosecuting cases of domestic abuse provides advice on how to proceed in cases involving those who sell sex and how to identify controlling or coercive behaviour.

Guidance by Offence:

Loitering or Soliciting for Prostitution - Relevant Law

Section 1(1) of the Street Offences Act 1959 (amended by Section 16 of the Policing and Crime Act 2009) makes it a summary-only offence for a person persistently to loiter or solicit in a street or public place for the purposes of offering services as a prostitute.

Section 1(4) specifies that for the purposes of Section 1, conduct is ‘persistent’ if it takes place on two or more occasions in any period of three months.

To demonstrate ‘persistence’, two officers need to witness the activity and administer the non-statutory ‘prostitute’s caution’. This caution differs from ordinary police cautions in that the behaviour leading to a caution may not itself be evidence of a criminal offence and there is no requirement for a person to admit guilt before being given a prostitute’s caution. Details of ‘prostitute’s cautions’ are recorded at the relevant local police station. Insertion of the word ‘persistently’ provides opportunities for the police to direct the individual to non-criminal justice interventions.

As the offence requires proof that the activity was ‘persistent’, there is a need to particularise when and where such activity took place. Once conduct has formed the basis of a prosecution, the same conduct cannot be included in the scope of any later prosecution. Furthermore, once an offender’s cumulative conduct is met by a finding of guilt in a criminal court; there is a wiping clean of the slate. Therefore, a caution or conditional caution will wipe the slate clean (see penalty/charging practice and conditional cautions below).

Section 1 of the Street Offences Act was amended by section 68(7) of the Serious Crime Act 2015, so that the offence of loitering or soliciting applies only to persons aged 18 or over. In so doing, it recognises children as victims in such circumstances.

Sentencing

This offence is punishable by a fine not exceeding level two on the standard scale. For an offence committed after a previous conviction, this increases to a fine not exceeding level three on the standard scale.

Section 17 of the Policing and Crime Act 2009 introduced orders requiring attendance at meetings as an alternative penalty to a fine for those convicted under Section 1(1). The Court may deal with a person convicted of this offence by making an order requiring the offender to attend three meetings with a supervisor specified in the order or with another person as the supervisor may direct. The purpose of the order is to assist the offender, through attendance at those meetings, to address the causes of prostitution and find ways to cease engaging in such conduct in the future. Prosecutors should, when appropriate, remind the Court of the availability of the order following conviction.

Where the court is dealing with an offender who is already subject to such an order, the Court may not make a further order under this section unless it first revokes the existing order.

Section 18 of the Policing and Crime Act 2009 amends Section 5 of the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974 for those sentenced to such an order. When the order has been completed, the person will have become a rehabilitated person under the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act.

Subject to the circumstances of the individual case, a conditional caution with a condition to attend a Drug Intervention Program (DIP) and a drug rehabilitative condition attached may be considered appropriate. A DIP condition can be tailored to best suit each individual, their drug use and nature of offending and can be used to help an individual avoid a criminal record. However, one of the issues that prevent this being used more frequently is that a restrictive condition must also be put in place when a conditional caution is imposed to prevent re-offending. Many of those who sell sex will not accept a caution if it restricts them from continuing to loiter or solicit in the same areas.

Keeping a Brothel

- Relevant Law

The following are summary-only offences under the Sexual Offences Act 1956:

- Section 33 - keeping a brothel;

- Section 34 - a landlord letting premises for use as a brothel;

- Section 35 - a tenant permitting premises to be used as a brothel.

- Section 36 - a tenant permitting premises to be used for prostitution.

Section 33A of the Sexual Offences Act 1956 (inserted by Sections 55(1) and (2) of the Sexual Offences Act 2003) creates an either-way offence of keeping, managing, acting or assisting in the management of a brothel to which people resort for practises involving prostitution (whether or not also for other practices).

There is no statutory definition of a ‘brothel’. However, it has been held to be “a place where people of opposite sexes are allowed to resort for illicit intercourse, whether…common prostitutes or not”:Winter v Woolfe [1931] KB 549.

It is, therefore, not necessary to prove that the premises are in fact used for the purposes of prostitution, which involves payment for services rendered. Sections 33 – 35 apply to premises where intercourse is offered on a non-commercial basis as well as where it is offered in return for payment.

Section 33A, however, only applies to premises to which people resort for practises involving prostitution (whether or not also for other practices). ‘Prostitution’ has the meaning given by Section 54(2) of the Sexual Offences Act 2003.

Section 33A was introduced to increase the maximum penalty for the exploitation of prostitution and to cover the circumstances where the element of control required for Section 53 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (‘controlling prostitution for gain’) is difficult to prove because the owner of a brothel has put himself / herself at a distance from the actual running of the establishment.

Section 6 of the Sexual Offences Act 1967 provides that “premises which are resorted to for the purposes of lewd homosexual practices shall be treated as a brothel” for the purposes of Sections 33 to 35 of the Act. The same now applies to Section 36 by virtue of Schedule 1 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003.

“It is not illegal to sell sex at a brothel provided the sex worker is not involved in management or control of the brothel. A house occupied by one woman and used by her alone for prostitution, is not a brothel”:Gorman v Standen,Palace Clarke v Standen (1964) 48 Cr App R 30.

“Premises only become a brothel when more than one woman uses premises for the purposes of prostitution, either simultaneously or one at a time”: Stevens v Christy [1987] Cr. App. R. 249, DC. This implies that if two women are present, both must be there for the purposes of prostitution. In circumstances where prostitutes are working individually out of one flat but there is a rotation of occupants and the young women are moved on a regular basis, it does constitute a brothel.

However, where rooms or flats in one building are let separately to different individuals offering sexual services, it may be treated as a brothel only if the individuals are effectively working together. Donovan v Gavin [1965] 2 QB 648 established that “the letting of individual rooms in a house under separate tenancies and to different prostitutes does not necessarily preclude the house, or parts of it, from being a brothel”.

It is not necessary to prove that full sexual intercourse is offered at the premises. It is sufficient to prove that “more than one woman offered herself as a participant of physical acts of indecency for the sexual gratification of men”: Kelly v Purvis [1983] QB 663.

The degree of coercion, both in terms of recruitment and subsequent control of a prostitute’s activities will be relevant to sentencing.

Charging Practice

When considering charges, the following public interest aims and considerations should be considered:

The need to penalise those who organise the selling of sex and make a living from the earnings.

Generally the more serious the incident the more likely that a prosecution will be required.

The vulnerability of those who sell sex and the position of those living off their earnings will be relevant.

If there is sufficient evidence, it will usually be in the public interest for brothel keepers to be prosecuted, particularly in circumstances where they are making significant financial gain from the enterprise.

Maids

When considering charging so-called ‘maids’ (an individual who has assisted in running the brothel, such as a receptionist), and there is sufficient evidence, the public interest will usually mean the maid will be charged if their assistance is crucial to the operation of the brothel or they have been involved for a long period of time. If the assistance of the ‘maid’ is minor or over a short period of time, such as cleaning and tidying, a prosecution may not be necessary in the public interest.

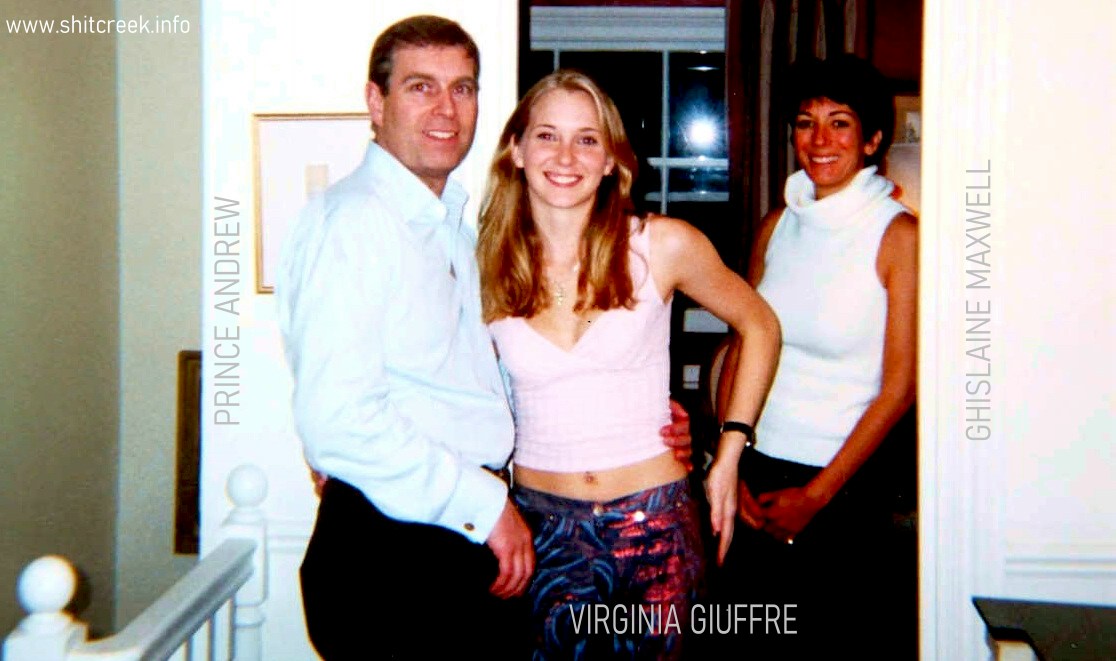

Being

a friend of a woman who is connected with a known sex offender, does not

make the former Prince guilty of a crime. If, as it appears may be the

case, the Duke has in the past been more than just a friend to Ms

Maxwell, that may explain why he stood by her in difficult times.

Especially with a reputation like Randy

Andy's. But according to the law as set out on the CPS (UK

Government) website, it does appear that Andrew

Mountbatten-Windsor

should be at the very least questioned as to having sex with Virginia

Giuffre, where she was 17, and 18 is the age limit where trafficking is

involved. He only needed to suspect that sex for money was involved, to

be convicted. According to an article in the Evening Standard, socialite

Lady

Victoria Hervey is quoted as

saying that Andrew frequented social gatherings organised

by Ghislaine

Maxwell. Nobody being above the law. The suggestion has

been made by Paul Page, a former security officer at

Buckingham Palace, that himself and other officers believed

Andrew and Ghislaine may have been an item.

The following models may provide a useful guide in assessing the involvement of the ‘maid’ in assisting in the running of the brothel:

Minor Involvement: The ‘maid’ is employed to look after those supplying sexual services. The ‘maid’ will keep the premises clean, buy provisions such as food and cleaning materials and ensure that items such as condoms, creams etc. are available. They will deal with calls for appointments from 'punters', answer the door and general reception duties. The ‘maid’ will be paid by those selling sex on a commercial basis.

Medium Involvement: This type of brothel has a maid who is brought in to manage premises used by several people selling sex over the course of a week. The ‘maids’ may differ and will be employed by the premises owner. The ‘maid ‘will not always know those who sell sex in the premises as they may also change daily. The ‘maid’ will be paid a small sum by the premises owner and more by those providing the services. They will vet 'punters' and receive telephone calls. Those selling sex in these brothels are likely to be foreign nationals and Prosecutors should be alert to the possibility that they may have been trafficked.

Where trafficked victims and children are providing sexual services in these premises, arrest and prosecution of the ‘maid’ should be considered.

Serious Crime Involvement: In this type of brothel, the ‘maid’ is actually the ‘controller’ or ‘trafficker’ works directly on the premises. Those selling sex in the brothel are often trafficked and/or coerced into providing a range of services to which they may not agree. The ‘controller’ maintains close supervision to limit their freedom and monitor their earnings and finances. Often these ‘maids’ are committing serious additional offences, e.g. trafficking for sexual exploitation, controlling prostitution for gain, false imprisonment. In these cases, a prosecution is more likely to be required.

However, it is also recognised that a way out of controlled or forced prostitution for some is to become part of the controlling network themselves. A ‘maid’ or brothel keeper in these circumstances may then be both a victim and an offender. In cases where trafficking is involved, Prosecutors should refer to the Human Trafficking Legal Guidance on ‘suspects who might be victims of trafficking’. In cases that do not involve trafficking, Prosecutors should carefully consider whether the public interest requires a prosecution. This will involve balancing the control or coercion to which the offender has been subjected against the harm that has been caused to their victims.

Sentencing

Sections 33 to 36 are summary-only offences. Without a previous conviction, sentences carry up to 3 months imprisonment, a fine not exceeding level 3, or both. For an offence committed after a previous conviction, they carry a maximum sentence on conviction of 6 months imprisonment, a fine not exceeding level 4, or both. Sections 33and 34 are ‘lifestyle offences’ within Schedule 2 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002.

Section 33A is an either-way offence and has a maximum penalty of 7 years imprisonment on indictment or 6 months upon summary conviction, or a fine not exceeding the statutory maximum (£5,000), or both.

Paying for Sexual Services

- Relevant Law

Section 53A of the Sexual Offences Act 2003, inserted by Section 14 of the Policing and Crime Act 2009, creates a summary-only offence of paying for the sexual services of a prostitute subjected to force, etc.

A person (A) commits an offence if:

A makes or promises payment for the sexual services of a prostitute (B);

A third person (C) has engaged in exploitative conduct of a kind likely to induce or encourage B to provide the sexual offences for which A has made or promised payment; and

C engaged in that conduct for or in the expectation of gain for C or another person (apart from A or B).

It is irrelevant:

- Where the sexual services are provided.

- If the sexual services are, in fact, provided.

- Whether A is, or ought to be, aware that C has engaged in exploitative

conduct.

‘Exploitative conduct’ includes:

The use of force, threats (whether or not relating to violence) or any other form of coercion.

Any form of deception.

The offence is one of strict liability. This means that it is irrelevant whether A is, or ought to be, aware that B is subject to exploitative conduct by C.

There is no statutory definition of ‘sexual services’. It is normally deemed to include acts of penetrative intercourse (as set out in section 4(4) Sexual Offences Act 2003) and masturbation. It does not include activities such as ‘stripping’, ‘lap dancing’ etc.

‘Prostitute’ is defined in Section 54(2) of the Sexual Offences Act 2003 as:

“A person who, on at least one occasion and whether or not compelled to do so, offers or provides sexual services to another person in return for payment or a promise of payment to that person or a third person.”

‘Gain’ means any financial advantage, including the discharge of an obligation to pay or the provision of goods and services (including sexual services) gratuitously or at a discount; or the goodwill of any person which is or appears likely, in time, to bring financial advantage.

Charging Practice

This offence was introduced to address the demand for sexual services and reduce all forms of commercial sexual exploitation. It has been developed, in part, to enable the UK to meet its international legal obligations to discourage the demand for sexual services in support of Conventions to suppress and prevent trafficking for sexual exploitation.

It is likely that this offence will be considered in relation to off-street prostitution. If the police apprehend someone who has paid for sexual services with a person involved in street prostitution, charging the buyer with soliciting (Section 51(A) Sexual Offences Act 2003) may be a more appropriate offence as this does not require proof of exploitative conduct.

The offence is most likely to arise in police brothel raids where there is enforcement against suspects controlling or exploiting prostitution for gain and where clients are apprehended in the operation. However, the offence is not limited to particular types of premises. It could therefore apply to premises which may have a legitimate business, for example a nightclub, as well as on-line internet based services.

In considering this offence, the previous history of the buyer may be a relevant consideration when applying the public interest test in the Code.

Sentencing

A person guilty of an offence under this section is liable on summary conviction to a fine not exceeding level 3 on the standard scale.

“Kerb Crawling”

- Relevant Law

Section 51A of the Sexual Offences Act 2003 (as amended by Section 19 of the Policing and Crime Act 2009) creates a summary-only offence for a person in a street or public place to solicit another for the purpose of obtaining a sexual service. The reference to a person in a street or public place includes a person in a motor vehicle in a street or public place.

This replaces the offences of kerb crawling and persistent soliciting under Sections 1 and 2 of the Sexual Offences Act 1985. The amendment removes the requirement to prove persistence. This enables an offender to be prosecuted on the first occasion they are found to be soliciting, without the need to prove persistent behaviour, or that the behaviour was likely to cause annoyance or nuisance to others.

Charging Practice

Although a matter for individual CPS Areas, an approach may be agreed with the police that is tailored to local circumstances, which provides an appropriate response to the local prevalence of kerb crawling.

National policing guidance advises that forces may give consideration to environmental solutions to encourage those involved in street prostitution to work in areas that are well lit and where CCTV is in operation. Enforcement on either those selling sex or ‘customers’ in cars or on foot is not encouraged as this is likely to result in displacement and put those selling sex at greater risk.

Sentencing

A person guilty of an offence under this section is liable on summary conviction to a fine not exceeding level 3 on the standard scale.

On conviction, in appropriate cases, the Prosecutor should consider drawing the Court’s attention to any relevant statutory provisions relating to ancillary orders for “kerb crawling”. These include powers to disqualify from driving under section 146 of the Powers of Criminal Courts (Sentencing) Act 2000 or to deprive an offender of property used to commit or facilitate the offence under Section 143 Powers of Criminal Courts (Sentencing) Act 2000.

Advertising - Placing of Adverts in Telephone Boxes

Section 46(1) of the Criminal Justice and Police Act 2001 creates a summary-only offence to place advertisements relating to prostitution. A person commits an offence if he:

Places on, or in the immediate vicinity of, a public telephone an advertisement relating to prostitution, and

Does so with the intention that the advertisement should come to the attention of any other person or persons.

Under Section 46(3) any advertisement which a reasonable person would consider to be an advertisement relating to prostitution shall be presumed to be such an advertisement unless it is shown not to be.

‘Public telephone’ is defined in section 46(5) as any telephone which is located in a public place and made available for use by the public. ‘Public place’ means any place to which the public have or are permitted to have access, whether on payment or otherwise. There are specific restrictions preventing the use of Section 46 where the advertisement is placed in a place to which children under 16 are not permitted to have access, whether by law or otherwise, or in any premises which are wholly or mainly used for residential purposes.

Sentencing

A person guilty of an offence under this section is liable on summary conviction to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 6 months or to a fine, or both.

Advertising - Placing of Advertisements in Newspapers

Whilst there is no specific offence, the Newspaper Society has advised publishers not to publish advertisements for illegal establishments such as brothels or for the illegal offering of sexual services. The advice also warns publishers that massage parlours can disguise illegal offers of sexual services and it suggests adopting protective policies such as checks on qualifications to ensure the advertised service is legitimate.

It advises that a newspaper company can adopt a policy of refusing all advertisements for personal services, or policies intended to reduce the risk of publication relating to illegal prostitution and human trafficking. Guidance advises that a newspaper company ensures that its staff are assisted and supported in decisions to refuse this type of advertising or refuse any particular advertisement. In some circumstances the newspaper itself may be liable to prosecution for money laundering offences under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002. See Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, elsewhere in the Legal Guidance.

Exploitation of Prostitution - Causing or Inciting Prostitution for Gain: Section 52 Sexual Offences Act 2003

Under Section 52(1) a person commits an offence if:

a) He intentionally causes or incites another person to become a prostitute in any part of the world, and

b) He does so for or in the expectation of gain for himself or third party.

‘Causing’ requires the prosecution to prove that the defendant contemplated or desired that the act would ensue and it was done on his express or implied authority or as a result of him exercising control or influence over the other person: Att.-Gen of Hong Kong v Tse Hung-lit [1986] A.C. 876 PC.

This offence is aimed at individuals who cause prostitution through some form of “fraud or persuasion” – Christian (1913) 23 Cox C.C. 541.

A Section 52(1) offence cannot be committed if the complainant has already been involved in prostitution, either home or abroad – R v Ubolcharoen [2009] EWCA Crim 3263.

Controlling Prostitution for Gain: Section 53 Sexual Offences Act 2003

Under Section 53(1), a person commits an offence if:

- He intentionally controls any of the activities of another person relating to that person’s prostitution in any part of the world, and

- He does so for or in the expectation of gain for himself or a third party.

Section 56 and Schedule 1 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003 extend the gender specific prostitution offences to apply to both males and females equally.

‘Gain’ is defined in Section 54(1) as:

Any financial advantage, including the discharge of an obligation to pay or the provision of goods or services (including sexual services) gratuitously or at a discount; or

The goodwill of any person which is or appears likely, in time, to bring financial advantage.

‘Prostitute’ is defined in Section 54(2) as:

“A person (A) who, on at least one occasion and whether or not compelled to do so, offers or provides sexual services to another person in return for payment or a promise of payment to A or a third person; and ‘prostitution’ is to be interpreted accordingly.”

‘Control’ includes, but is not limited to, ‘compulsion’, ‘coercion’ and ‘force’. It is enough that the person acted under the instructions or directions of the Defendant. There is a wide variety of possible reasons why the person may do as instructed. It may be, for example, because of emotional blackmail or the lure of gain. There is no requirement for the person to have acted without free will: R v Massey [2008] 1 Cr. App. R. 28 CA.

An individual who profits from the activities of a prostitute but who does not control any of those activities will fall outside of the scope of this offence: R v Massey

The following types of conduct have specifically been held to fall outside of the scope of this offence:

Selling a directory of prostitutes, in which the prostitutes paid to have their details included: Shaw v DPP [1962]

A.C. 220.

Providing prospective clients, for a fee, with information about services offered by named prostitutes: R

v Ansell [1975] Q.B. 215

Charging Practice

These offences focus on situations where the complainant has been sexually exploited by others for commercial gain. Sexual exploitation can occur in both on and off-street prostitution. The offences are designed to tackle those who recruit others into prostitution for their own gain or someone else’s regardless of whether this is achieved by force or otherwise.

The offences are primarily aimed at those who cause, incite or control others who are over 18 to become a ‘prostitute’. Offences involving children under 18 should be considered under Sections 47, 48, 49 and 50 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003, which carry a higher penalty. However, where the prosecution may have difficulty proving that the Defendant did not reasonably believe that the child was 18 or over, then Section 52 or Section 53 may be charged to ensure that the offender does not escape liability altogether.

When considering charge, in addition to the public interest factors set out in the Code for Crown Prosecutors, the following public interest aims and considerations should be considered:

- To prevent people leading or forcing others into prostitution;

- To penalise those who organise ‘prostitutes’ and make a living from their earnings;

- The vulnerability of those selling sex and the position of those living off the earnings will clearly be relevant;

- Generally, the more serious the incident the more likely that a prosecution will be required.

If there is sufficient evidence to satisfy the evidential stage of the Full Code Test, it is likely it will be in the public interest to prosecute.

Given the high profits from organised prostitution offences, financial investigation is important to provide evidence to support these offences as well as proceedings for asset seizure under the Proceeds of Crime Act.

Sentencing

The offences are either-way and are specified sexual offences in respect of which a sentence of imprisonment for public protection may be imposed under the Criminal Justice Act 2003. On summary conviction, a person is liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 6 months or a fine not exceeding the statutory maximum or both. On conviction on indictment, a person is liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 7 years.

Both offences are ‘lifestyle offences’ for the purposes of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002.

Police Investigations: Abuse of Process

In investigating cases of controlling prostitution, the police may raid and disrupt brothels where local police policy previously had been one of toleration.

Such an investigation in 2007 resulted in Defendants, who were arrested and charged with offences of controlling prostitution, raising a successful defence of abuse of process based on entrapment and breach of an undertaking (implied or otherwise) given by the police not to prosecute.

The Crown Court concluded that, by their words and acts, the police had led those who were running the brothels into believing that, provided certain conditions were met, the premises could continue to operate as brothels without risk of prosecution. The police had openly pursued a ‘laissez faire’ policy towards them, and clear undertakings had been given by the police that they would not investigate those running the brothels provided that certain ‘ground rules’ were observed. These included no selling of alcohol, no drugs and no under-age girls. Involvement of the local authority in licensing these establishments for the purposes of the sale of alcohol, which went unchallenged by the police, served to reinforce this policy and the impression created for those running them: R v Elsworth and others (Operation Rampart) 2007

When reviewing a similar case, to prevent an abuse of process argument based on breach of an undertaking, Prosecutors should advise the investigating officer to obtain:

- Police force (or other local) policy on policing off-street prostitution;

- Any further relevant guidance issued to that police force;

- Information as to whether there was toleration of off-street premises; and

- Evidence from the officers who allegedly visited the premises, providing detail of how often they visited, for what purpose, what was said and by whom.

Prosecutors should then carefully consider whether there is potential for an abuse of process of argument. Prosecutors should refer to Abuse of Process, elsewhere in the Legal Guidance, which sets out the relevant legal arguments in similar circumstances.

Trafficking for Sexual Exploitation: Section 2 Modern Slavery Act 2015

Section 2 of the Modern Slavery Act 2015 creates an offence of arranging or facilitating the travel of another person for the purposes of sexual exploitation. A person commits an offence if he arranges or facilitates the victim’s travel by recruiting them, transporting or transferring them, or harbouring or receiving them, with a view to the victim being exploited in any part of the world. For these purposes, exploitation involves the commission of an offence under Part 1 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003, or section 1(1)(a) Protection of Children Act 1978. It therefore captures all sexual offences including exploitation of prostitution.

Further information including charging practice can be found in Human Trafficking, Smuggling and Slavery elsewhere in the Legal Guidance.

Sexual Exploitation of Children

Children under

18, exploited in prostitution, should be treated as victims of abuse.

Those who sexually abuse children should be prosecuted under Sections 47 – 50 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003. See Abuse of Children through Prostitution or Pornography in the Sexual Offences Act 2003 – Guidance, elsewhere in the Legal Guidance. This covers the prosecution of those who coerce, exploit and abuse children through prostitution. These offences carry a higher penalty.

Consent is irrelevant. A reasonable belief that the child is over 18 affords a defence if the child is 13 or over. There is no defence of reasonable belief if the child is aged under 13.

If there is sufficient evidence, the public interest will usually require a prosecution if someone has sexually exploited child. In these cases, Prosecutors are encouraged to consider prosecuting strategies which do not require the victim to give evidence in court.

See also guidance on Extreme Pornography; Indecent and Prohibited Images of Children; Obscene Publications, elsewhere in the Legal Guidance.

'Sex for Rent' Arrangements and Advertisements

There have been, in recent times, an increase in reports of advertisements posted on classified advertising websites, such as Craigslist, where landlords offer accommodation in exchange for sex. Such arrangements can lead to the exploitation of highly vulnerable persons who are struggling to obtain accommodation.

When considering the approach to prosecuting this behaviour, it is essential to consider the definition of prostitution contained in section 54 Sexual Offences Act 2003:

‘(2) In sections 51A, 52, 53 and 53A “prostitute” means a person (A) who, on at least one occasion and whether or not compelled to do so, offers or provides sexual services to another person in return for payment or a promise of payment to A or a third person; and “prostitution” is to be interpreted accordingly.

(3) In subsection (2) and section 53A, “payment” means any financial advantage, including the discharge of an obligation to pay or the provision of goods or services (including sexual services) gratuitously or at a discount.’

Therefore, the provision of accommodation in return for sex is capable of being caught by the following legislation - section 52 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003 (causing prostitution for gain) and that an advertisement would also be unlawful in accordance with section 52 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003 (inciting prostitution for gain). Please see above for substantive guidance on sections 52 and 53.

Prosecuting ‘sex for rent’ arrangements via use of a Section 52 'causing' charge

Circumstances which clearly feature exploitation

Causing or controlling prostitution for gain charges can be considered where arrangements are in place which involve the exploitation of a victim, e.g. where a homeless or otherwise vulnerable person is persuaded to enter into an arrangement.

Prosecutors should be mindful that in certain cases the evidence may also highlight an absence of ‘free’ consent to sexual activity as in R v Kirk and Kirk [2008] EWCA Crim 434 (a case involving a vulnerable and destitute 14 year old girl who submitted to sex in return for money to buy food), which may give rise to the availability of other sexual offences such as rape.

Circumstances where exploitation is or may be absent

As the legislation is designed to address exploitation, there are potential difficulties in prosecuting arrangements where the element of exploitation is or may be missing; for example, a ‘sex for rent’ arrangement, which developed following a suggestion made by the tenant or prospective tenant. Such a scenario would call into question whether the landlord had ‘caused’ the tenant to become a prostitute. Similarly, there may be cases where the arrangement was discussed and agreed freely between two adults with full capacity in circumstances where there was no significant financial and/or power imbalance. The case of R v Christian (1913) 23 Cox C.C. 541, where a female willingly committed indecent acts, decided under old law, is likely to remain relevant. In circumstances where a victim has apparently acted in accordance with his/her free will, a section 53 ‘controlling’ charge could be considered.

Prosecuting ‘sex for rent’ arrangements via use of a Section 53 ‘controlling’ charge

A section 53 ‘controlling’ charge may be capable of capturing established ‘sex for rent’ arrangements, even where the victim is apparently acting in accordance with his/her own free will.

Prosecuting individuals for posting ‘sex for rent’ advertisements via use of a Section 52 ‘incitement’ or ‘attempted incitement’ charge

The use of a section 52 ‘incitement’ or ‘attempted incitement’ charge to prosecute individuals who post offending advertisements may face the following difficulties:

Proving that an advertisement came to the attention of a potential victim Incitement can only be established if the proposed activity came to the attention of a potential victim. It is unlikely that posting an advert for general viewing would amount to the incitement of another person. What if the prosecution could not establish that anyone had looked at the advert or that only prostitutes had looked at the advert?

Proving that the posting of an advertisement is ‘more than merely preparatory’ to incitement for the purposes of an attempt In order to prove an ‘attempted section 52’ offence the prosecution must establish that the act of placing an advert was more than merely preparatory to causing or inciting another to become a prostitute. It is not clear how this could be proved to the criminal standard where it is not possible to establish the identity of a respondent to the advert.

Causing or Inciting Prostitution for Gain: Section 52 Sexual Offences Act 2003

Controlling Prostitution for Gain: Section 53 Sexual Offences Act 2003

Trafficking for Sexual Exploitation: Section 2 Modern Slavery Act 2015

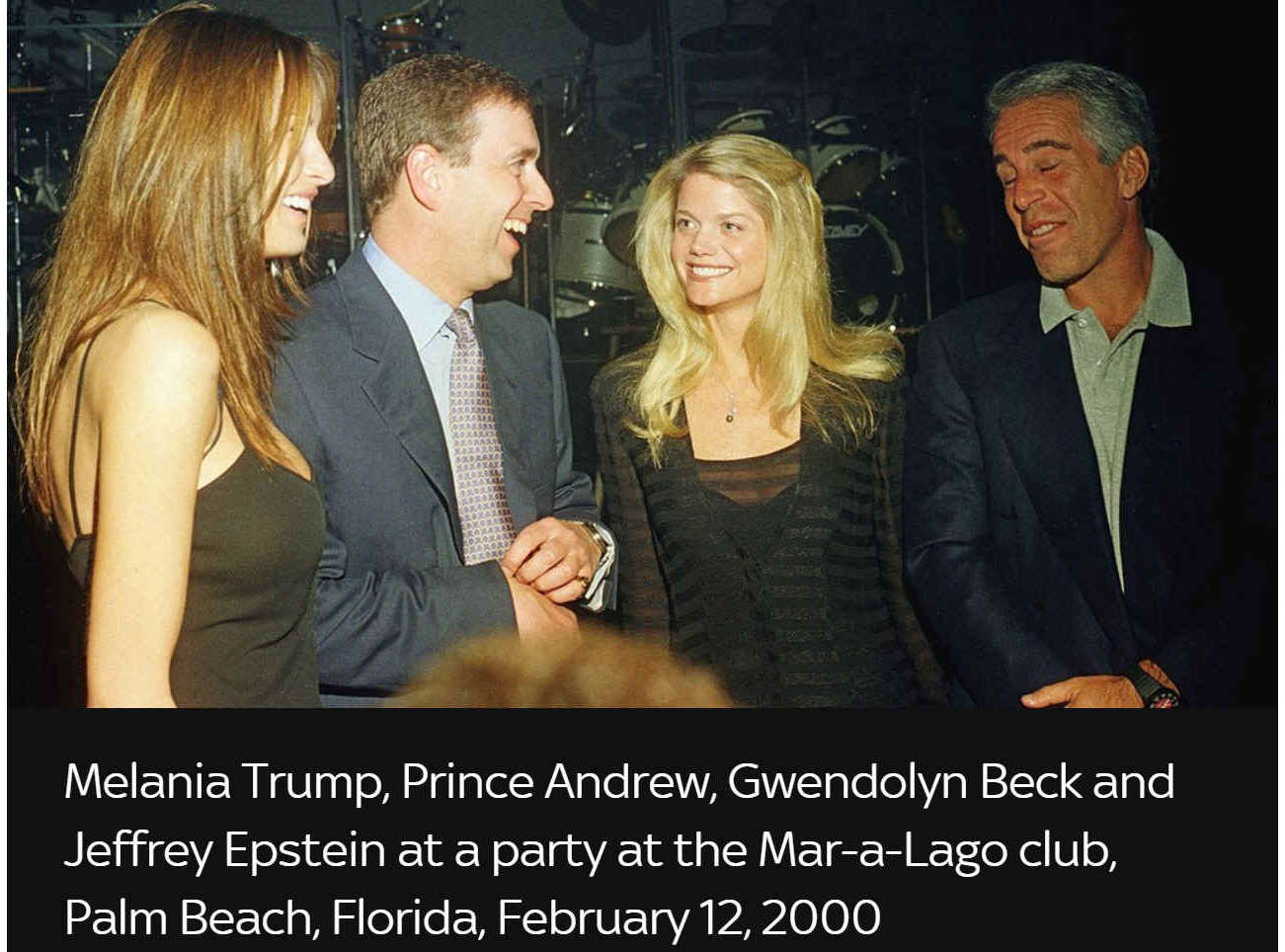

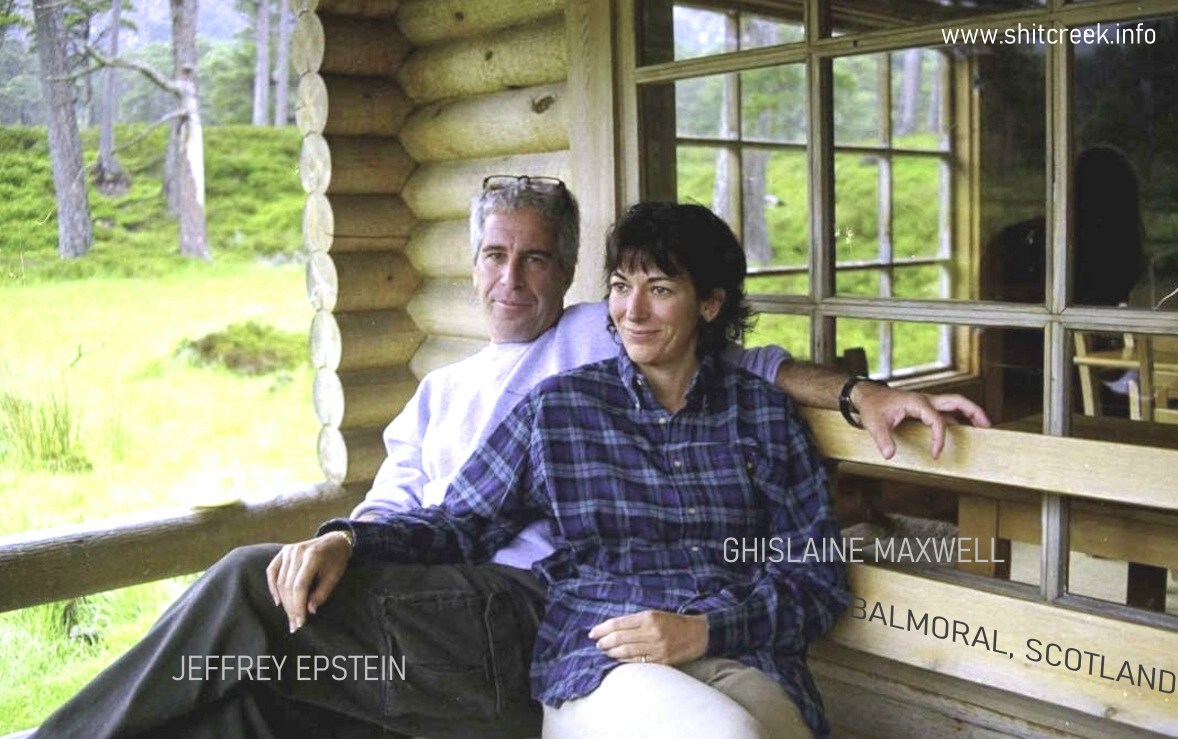

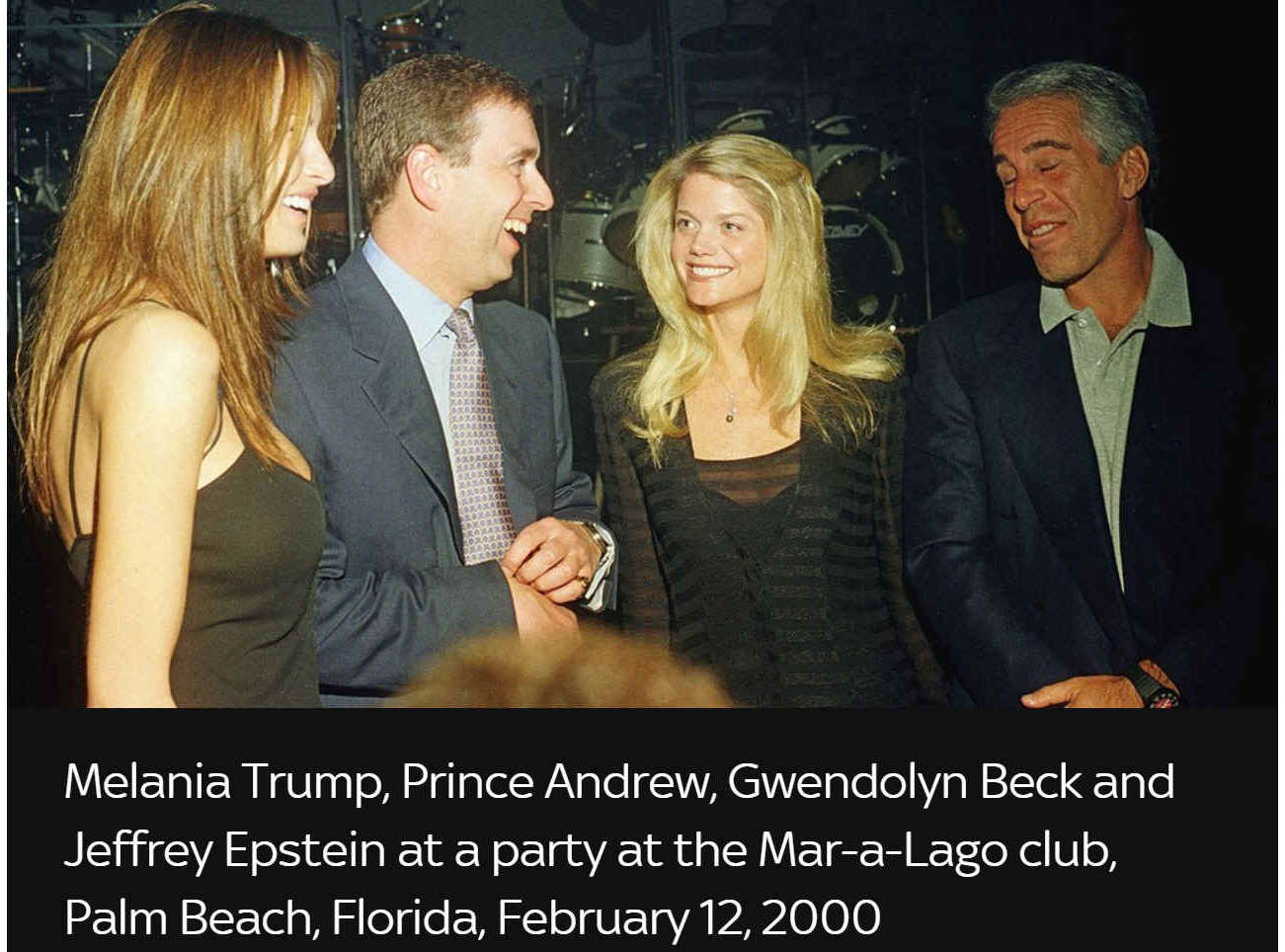

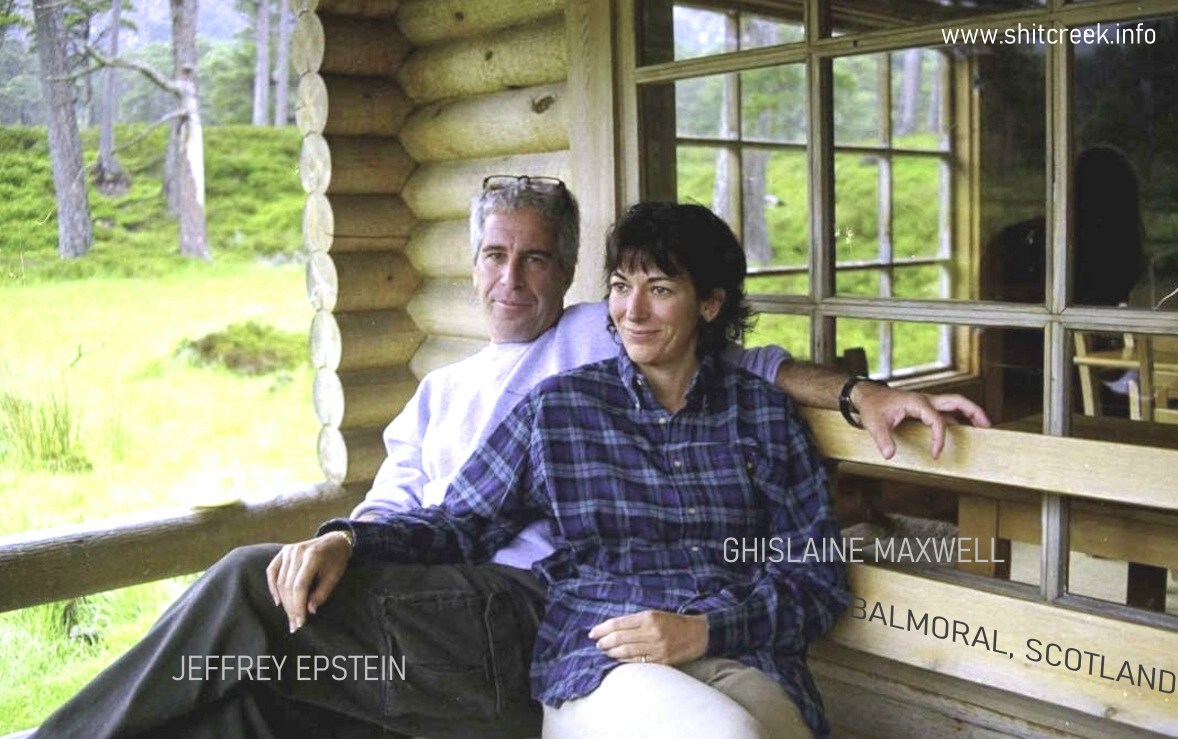

BALMORAL

OR IMMORAL - You would be persuaded by this picture, that Epstein

and Ms

Maxwell, were good friends of the Duke. On the other hand, Prince

Andrew was always entertaining big business, in promoting Great Britain

Ltd. It's hard to believe that a prostitute would pose for a picture and

be smiling, just as much as Ghislaine would allow a picture to be taken,

if she was effectively the Madam of a high class brothel.

If

the case against Prince Andrew is like a slow drip, drip of information,

none of which was good for him or the Monarchy, where in a modern

society, it is absurd that a person without any administrative gifts or

qualifications might inherit the reins to the country in a modern

democracy. It is high time that the cards were shuffled, in the

interests of the people who are suffering as a result of negligence on

the part of the Crown, in failing to secure affordable houses for the

electorate, cheap renewable energy and food at sensible prices - free of

plastic and toxins.

Prince Andrew & the Epstein Scandal: The Newsnight Interview - BBC News

- 4,840,669 views - 17 Nov 2019

In a Newsnight special, Emily Maitlis interviews the Duke of York as he speaks for the first time about his relationship with convicted paedophile Jeffrey Epstein and allegations which have been made against him over his own conduct.

The Duke of York speaks to Emily Maitlis about his friendship with Jeffrey Epstein and the allegations against him. In a world exclusive interview, Newsnight’s Emily Maitlis speaks to Prince Andrew, the Duke of York at

Buckingham

Palace.

NOW

IS THE TIME FOR CHANGE - Under the present system where the Head of

State is a royal, and there is no written

constitution, politicians like

David Cameron and Boris

Johnson can lie

with impunity - even to Queen

Elizabeth - and not face penalties. Police

officers can shoot unarmed civilians and not be sent to prison, and

planning officers can deceive the Secretaries of State and High Court

judges, and not be prosecuted. In effect, it is alleged that there is little justice in

England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. We aver that such

machinations are costing the ordinary taxpayer, Treasury and the Crown (being the

state) significant sums of money, while adding to the UK's carbon

footprint. Hence, the country is not being run effectively by the at

present;

defective administration, not to serve its citizens, but to sustain and

profit itself. Unlike the US

Constitution of 1791 that exists to serve

the people.

The Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator (OSCR) is examining fundraising practices at the Prince’s Foundation, following allegations that the Prince of Wales' closest former aide

co-ordinated with "fixers" over honours nominations for a Saudi billionaire donor.

Britain

is held to be the most corrupt country in the world when it comes to

laundering drug money.

LINKS

& REFERENCE

https://www.cps.gov.uk/legal-guidance/prostitution-and-exploitation-prostitution

https://www.politics.co.uk/reference/prostitution/

https://responsiblerobotics.org/2017/07/05/frr-report-our-sexual-future-with-robots/

https://www.dailystar.co.uk/news/latest-news/sex-robot-brothel-houston-texas-16793833

https://www.cps.gov.uk/legal-guidance/prostitution-and-exploitation-prostitution

https://www.politics.co.uk/reference/prostitution/

Please use our A-Z

INDEX to navigate this

site